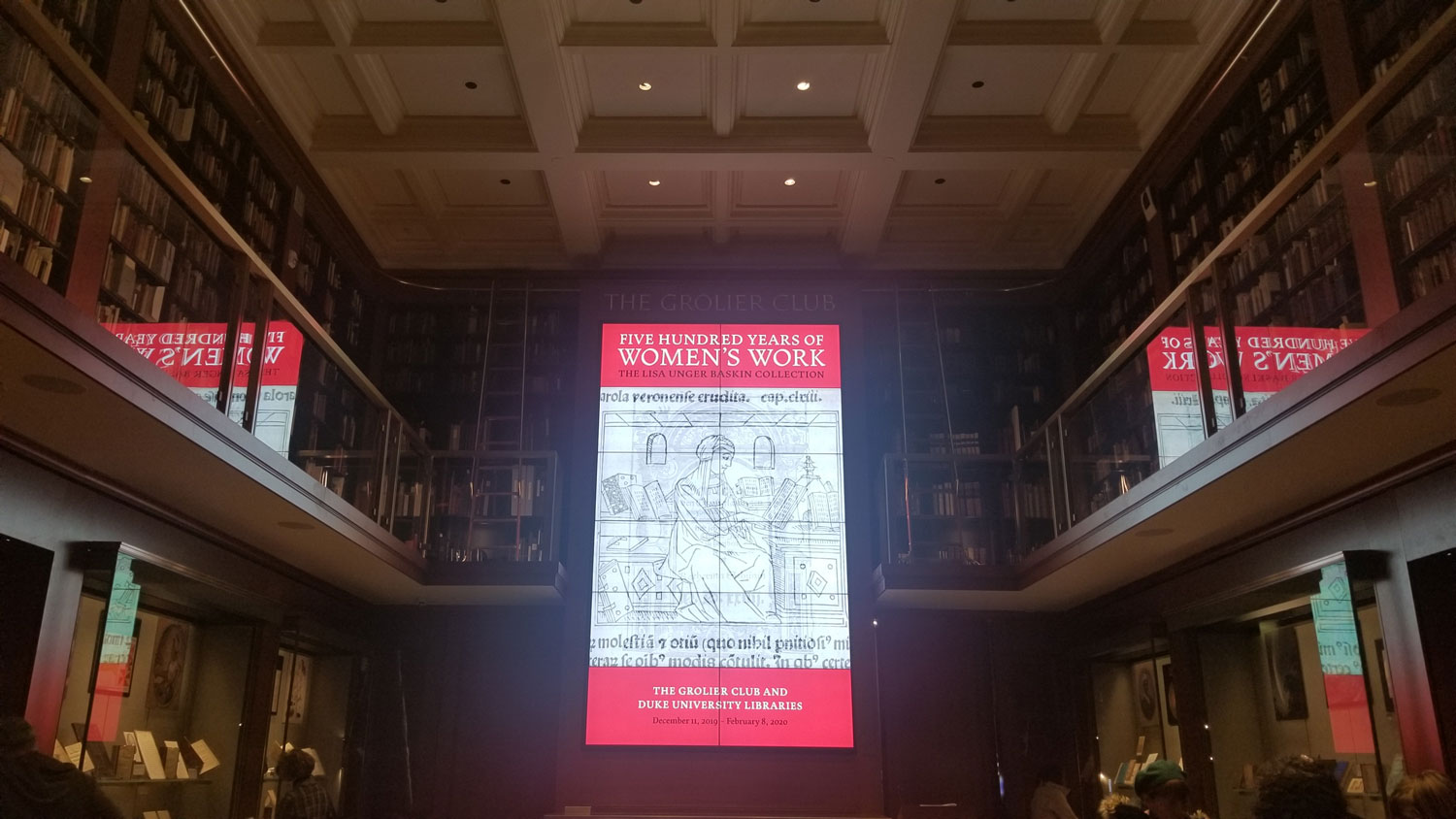

Nestled behind a Romanesque-inspired Methodist Church on 59th St and Park Avenue, entering the Grolier Club conjures a spiritual experience. A private club for the most esteemed bibliophiles, many public exhibitions and lectures are offered in their first and second floor galleries. One day, you might even be granted access to the heavenly third floor, aka the Holy Grail of All Things Bookish: the Grolier Club Library (ok, ok, all you really have to do is ask).

Main exhibition hall at the Grolier Club / my preferred house of worship.

If you consider yourself a typophile, or a bibliophile or any sort of sentient being, then you have less than a month (it closes February 8, 2020) to visit the current exhibition, “Five Hundred Years of Women’s Work: The Lisa Unger Baskin Collection”. Lisa Unger Baskin is a self-described collector of “stuff”, although that is really a gross understatement. While books are a major component of her collection, other kinds of printed ephemera — such as banners, currency, broadsides, and personal letters — celebrates the lives and labor of working women.

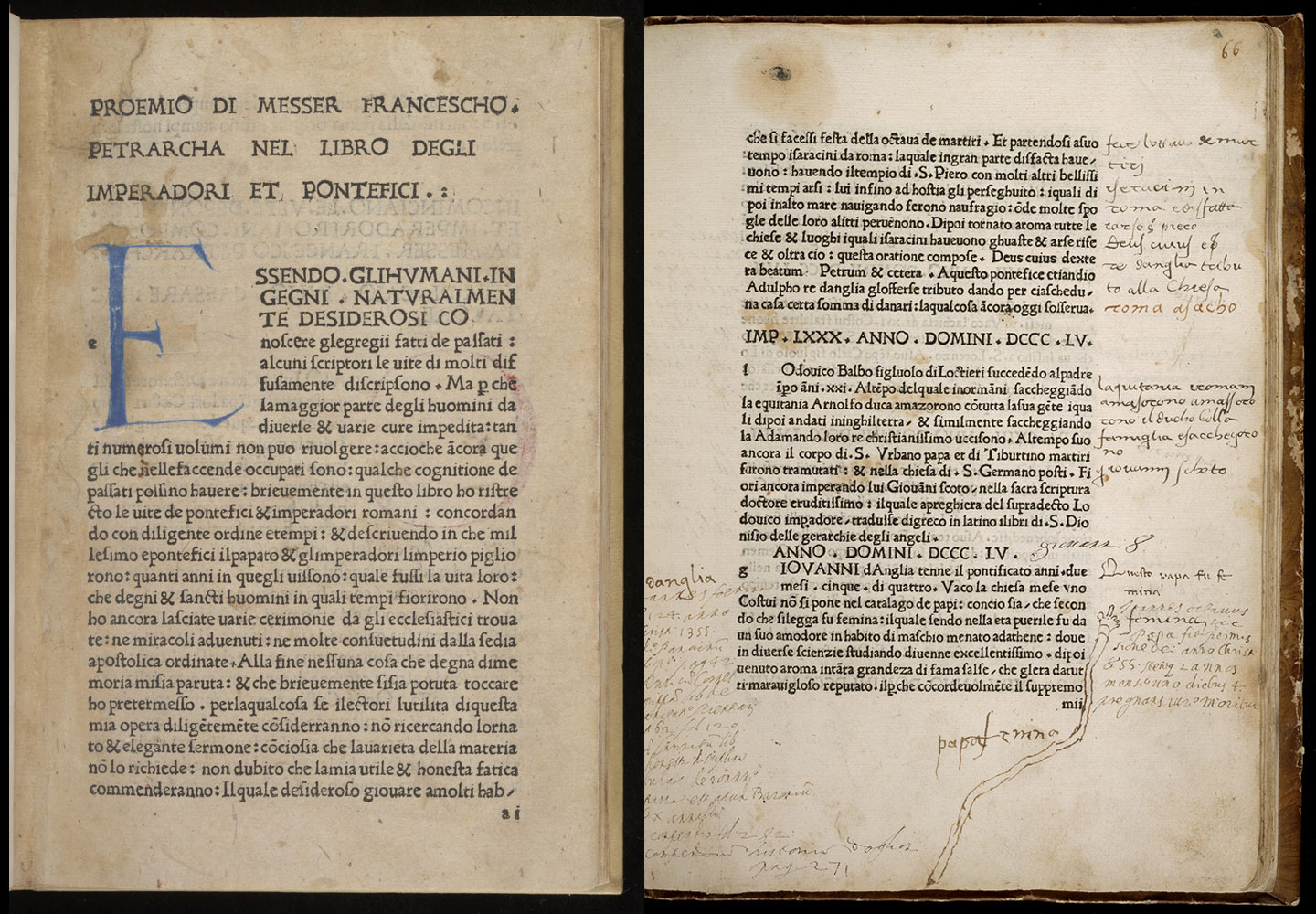

The exhibition, limited mostly to western Europe and the US, is organized chronologically and thematically. The exhibition begins in the year 1240 AD with a hand-scribed document granting land to build a house for “repentant prostitutes,” and concludes well into 20th century social reform movement publications. The earliest (at least in Europe?) printing by women is attributed to nuns at the Convent of San Jacopo de Ripoli in 1478, Tuscany, Italy. According to its label, “the nuns set type, sewed folios, and provided financial backing for the press.” Now those are my kind of nuns!

Petrarch [pseud.], Incominciano Le uite de pontefici et imperadori Romani, Florence: Apud Sanctum Iacobum de Ripoli, 1478, Lisa Unger Baskin Collection, Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University. Accessed January 11, 2020, https://exhibits2.library.duke.edu/exhibits/show/baskin/item/3935

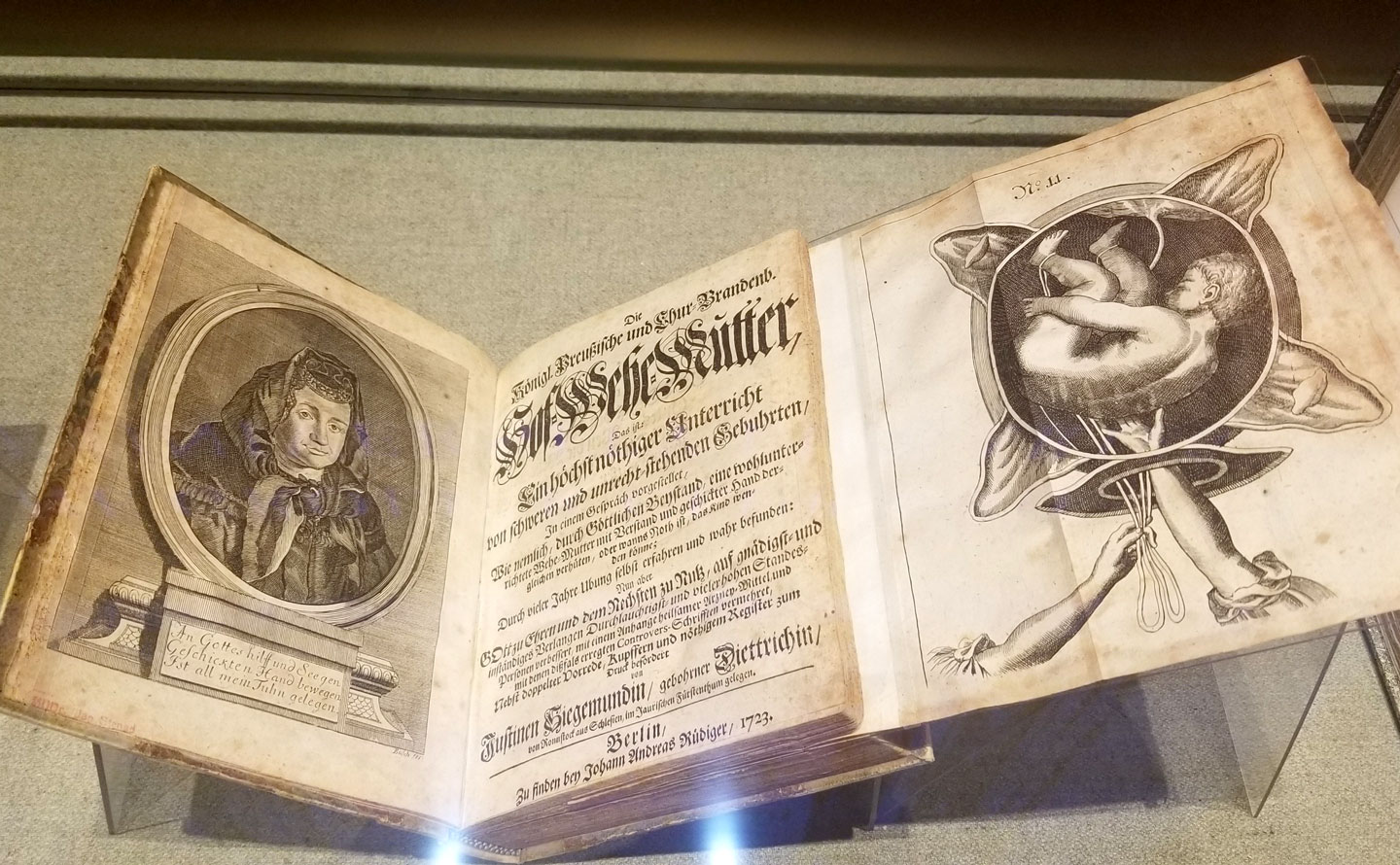

The work of midwives is well documented in the exhibition. Louise Bourgeois Boursier, the 16th century midwife of Marie de Medici, wrote Observations diuerses, sur la sterilité, perte de fruict, foecondite, accouchements, et maladies des femmes, et enfants nouueaux naiz , published 1642–1644. It was then translated into languages across Europe for over 100 hundred years after its original publication. The engraved illustrations from these obstetrics and midwifery books will either give you a few chuckles or countless nightmares. You choose! This foldout engraving on the right is a pretty accurate depiction of my second child’s birth story:

Siegemund, Justina, Die königl. Preussische und Chur-Brandenb. Hof-Wehe-Mütter, 1723. https://exhibits2.library.duke.edu/exhibits/show/baskin/item/4025

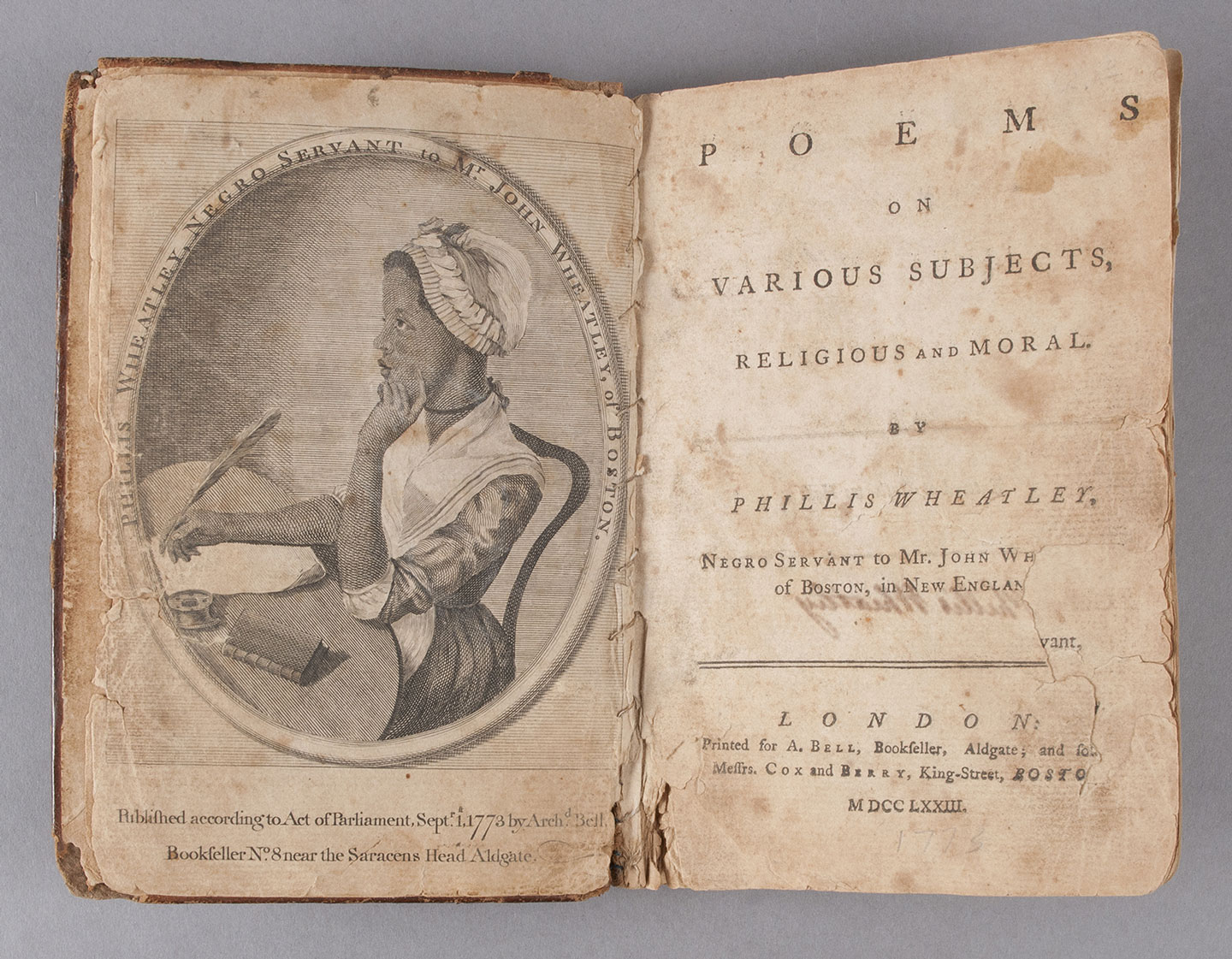

Baskin’s collection is greatly informed by her long history of social activism and tells the stories of women fighting for the abolition of slavery, voting rights, and reproductive health. A book of poems by Phillis Wheatley, an enslaved woman and one of the most well-known poets of the late 18th century American colonies, as well as books and correspondences by 19th century preacher and abolitionist Sojourner Truth, are not to be missed.

Wheatley, Phillis, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, London: Printed for A. Bell, 1773, Lisa Unger Baskin Collection, Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University. Accessed January 11, 2020, https://exhibits2.library.duke.edu/exhibits/show/baskin/item/4039

Suffragist paraphernalia rounds out the exhibition with their bold type and snarky imagery. The last case is filled with stunning bindings / eye candy from the late 18th-early to 19th century.

Only a small fraction of Baskin’s collection, which includes over 16,000 items and counting, is on display. She’s still collecting, although as she mentioned during the gallery tour I attended, it’s become a lot more challenging. She recounted the days when she’d go to book fairs, ask for things related to women, and uninterested sellers would point to an abandoned box of treasure. The rest of the collection can be found at the Duke University library, where Baskin donated it in 2015 (road trip, anyone?). If you can attend one of the last two free public tours lead by Lisa Unger Baskin herself, I highly recommend it. The exhibition catalogue, published by Oak Knoll Press, features an all-women design / production team (and type by women!).

I left the Grolier Club wanting to know more, not only about the women and the work in the exhibition, but also what was not there: particularly, work by women outside of the US and Europe or whose work has been marginalized by historical record. Still, it’s difficult to put into words the enormous significance of Baskin’s collection. Most importantly, it bares witness — through the printed page — to the vital contributions made by women to science, literature, history, medicine, politics, and society at large. Women have always worked. It’s our job to remember.

Five Hundred Years of Women’s Work: The Lisa Unger Baskin Collection is on display at the Grolier Club through February 8, 2020.