Although my professional area of focus is Indic type, by which I mean the Brahmi-derived scripts native to India, my favorite coins in my small collection are four 2 Anna coins from the Princely State of Hyderabad, minted in 1946. They are among the last coins minted by the Hyderabad State before its dissolution.

The Hyderabad State, which occupied the Deccan plateau of south-central India, was a semi-autonomous vassal state that existed alongside the British Raj from 1798 until India’s independence in 1947. Ruled by the Asaf Jahi Dynasty, which was Turkic in origin, the Hyderabadi government spread Persian culture in the region. While the British issued currency to be used throughout their South Asian empire, they allowed the Hyderabad State to issue its own set of banknotes and coins.

At the center of the coin is the Char Minar (four towers), an architectural marvel and mosque that is the symbol of the city of Hyderabad.

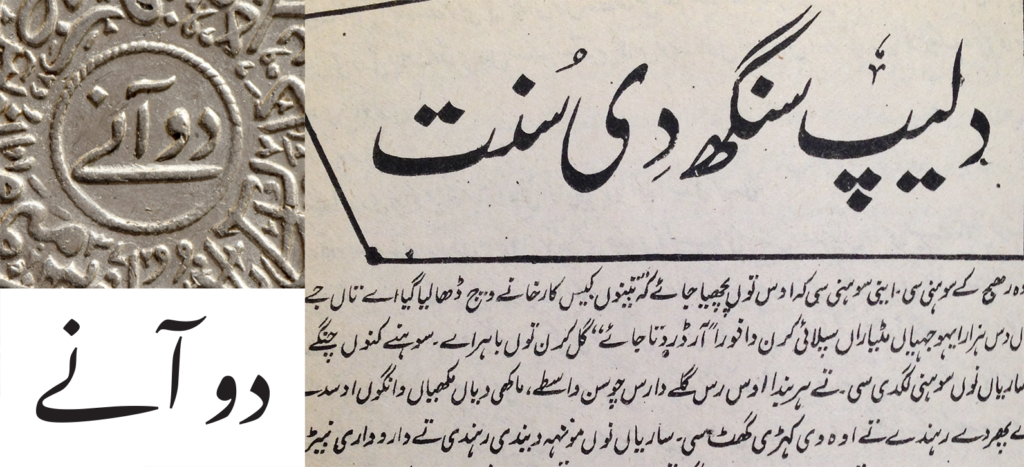

On the reverse, the denomination sits in the center, “Do Aane,” which means Two Annas. An anna was equivalent to 1/16 of a rupee. (India moved to a decimalized currency system, based on powers of 10, in the late 1950s.)

“Do” means “two” in both Persian and Dakhini, a dialect of Urdu and the language spoken by the Muslim population of the Hyderabad State. Though the vast majority of the citizens living in the Hyderabad State were Hindu, and spoke languages like Telugu, Marathi, and Kannada, nearly all of the feudal lords, civil servants, and members of the upper-class were Muslim and spoke either Persian or Dakhini. And as long as all of the land-owners, wealthy merchants, and tax-collectors could read the coins, why bother stamping the workers’ native languages onto each coin? The Nizams of Hyderabad certainly excelled at keeping money in their control. In fact, the Nizam who minted this coin, Osman Ali Khan, was reputed to be richest man in the world during his reign.

“Do Anne”, as rendered on the coin (top left), and in the font, Noto Nastaliq Urdu (bottom left). Handwritten Nastaliq headline and body copy (right) from an Urdu Punjabi magazine published in the mid-60s.

The denomination, “Do Aane”, is written in the Nastaliq style of Arabic script. Nastaliq is the most commonly-used style in South Asia, having originated in Iran in the 14th century, and spread by the Mughal Empire. The Nastaliq calligraphic hand is a fluid, cascading style, with letters that start at varying heights, dependent on the letters that follow it. This undulating baseline creates an extra level of complexity to the script. While it’s easily written by hand, it’s currently very difficult to emulate in a typeface. (Type designers and font editor engineers, take note!)

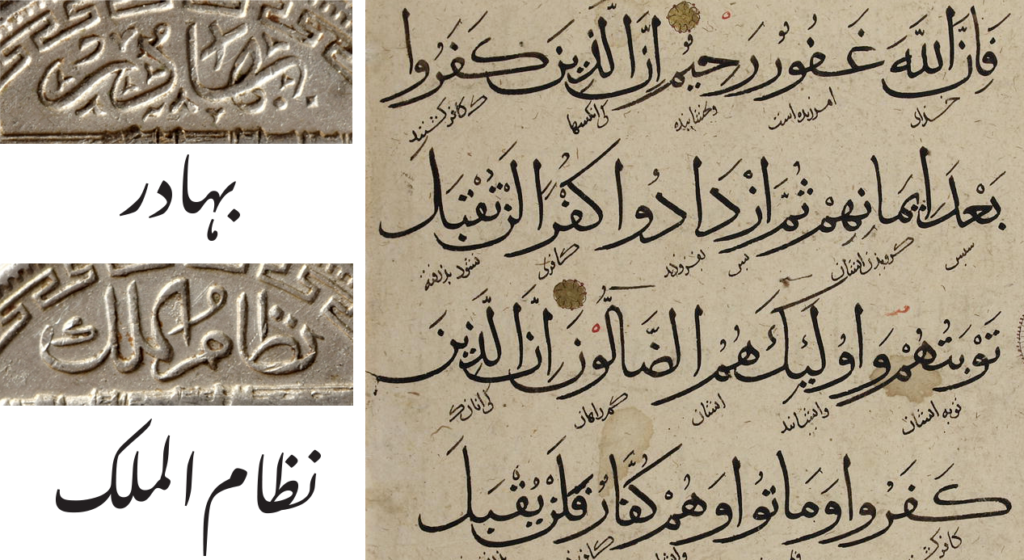

“Bahadur”, honorific term meaning “hero”, in unknown calligraphic style. Beneath it, the word transcribed in Noto Nastaliq Urdu. (top left) “Nizam Al-Mulk”, unknown calligraphic style, and as rendered by Noto Nastaliq Urdu. (bottom left) Sample of Tawqī script (right), as seen in a 14th century Quran, with Persian translations. *Please see comments below for additional transcriptions*

The other writing on the coin is definitely not Nastaliq, but something more flourished, with unusual ligating letter combinations, and dotted with ornaments. I asked Sahar Afshar, John Hudson, and Borna Izadpanah to help determine its script classification. The general consensus is that this might be considered Tawqī, which is a derivative of the ornamental style Thuluth, with notably shorter verticals. But no one felt confident. Why is it so hard to classify? “Coins are a special case in many scripts,” John explains, “…you might not get an exact match to a style in its manuscript form. The size of the object frequently means that proportions are adjusted to make text fit vertically, or unconventional ligation is used to fit it horizontally.”

That’s certainly the case with the reverse side of this coin. The script and ornaments are so tightly-fitted that they form an even texture with the negative space. The writing has crossed the line into abstract-pattern territory. And a beautiful one at that – resembling fine metal filigree work. This beautiful script work is why I believe it was saved from the melting pot.

The Hyderabad State was dissolved in 1956, and the territory was split up along linguistic lines. The Hyderabadi coins were demonetized, and the Indian Rupee, used by the rest of the nation, was adopted.

Before coins are demonetized, governments usually allow you to trade them in, for a limited time, for an equivalent of the replacement currency. But if any coins remain after this period, or, if the value of the metal contained in the coin exceeds that of the government’s declared value of the coin, they are often melted down and recast into something more useful. This especially is the case of coins made before the 1930s, when the world abandoned the gold standard. For most of human history, coins were made of high-concentrations of valuable metal like gold, silver, and copper. Now that fiat money rules the world, they are mostly made of nickel or zinc, metals worth only a fraction of the denomination printed on them.

But, if a coin’s design is exceedingly beautiful, or its history rich in sentimental value, it is saved. The Banjara people of India (also known as Lambada) are well-known for their intricate embroidery work and distinctive jewelry, often made from old coins. By soldering loops, bells, and embellishments onto old rupee, paise, pie, and anna coins, they create decorative brooches, pendants, and rings.

Lambadi woman (left), wearing traditional costume. Banjara jewelry and textiles being sold at a market stall. (right)

These discarded coins represent hundreds of years of economic oppression by the British Raj and the Nizam. After a hard-fought war for independence, these coins have been reduced to scraps of metal, and have been reclaimed and reinvented by artisans from a nomadic culture. The Banjaras can solder a flower or a spike over the name of an oppressive King, and use these relics to beautify themselves and show off their personal wealth. I was happy to purchase one of these rings, and wear it as a reminder of history and how we can shape the future.

This post is part of My 2¢, a short series on money-related type and lettering examples, stories and thoughts. You can read the rest of the series here.

The “unknown” script is definitely Thuluth with short ascenders, there is no doubt about this. The only thing unusual about it (apart from the short ascenders) is the looped part at start of the head of ح of حيدر and خ of فرخنده.

Thanks so much, Khaled. And thank you to Roozbeh Pournader who also engaged in the script classification discussion on Twitter, agreeing with Khaled that this is Thuluth.

Some reference images regarding the script discussion:

This compares Thuluth and Tawqi’: http://www.iranicaonline.org/uploads/files/Calligraphy/v4f7a004_f50_300.jpg

Here’s some sample of such ligatures from Thuluth: http://www.iranicaonline.org/uploads/files/Calligraphy/v4f7a004_f43_300.jpg

Roozbeh also tweeted some transcriptions of the coin that I want to share here with the other readers:

The text for Bahadur is best transcribed with Heh Doachashmee: بھادر

And Nizam Al-Mulk is closer to original using an Arabic Kaf: نظامالملك

The text between the towers reads آصفجاه (Asif Jah)

The text around 2 Anna reads: جلوس میمنتمأنوس ضرب فرخندهبنیاد حیدرآباد

Thank you both so much!

Just an FYI, the handwritten Nastaliq sample you posted does not look like Urdu. It is likely Punjabi written in the Shahmukhi alphabet.

Deepak, you’re right! This is an image from a bound magazine “Waris Shah” that was in the Urdu section of a library, but they must have mislabeled it. Thank you for spotting it!