“The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel,” Season 5, Episode 2.

The Job

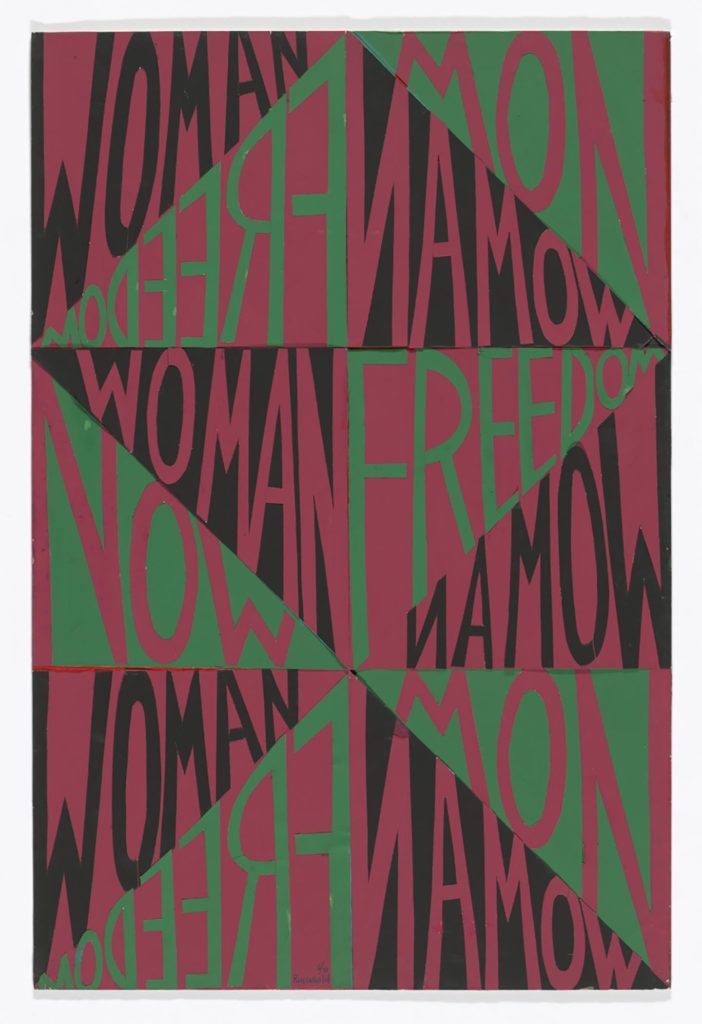

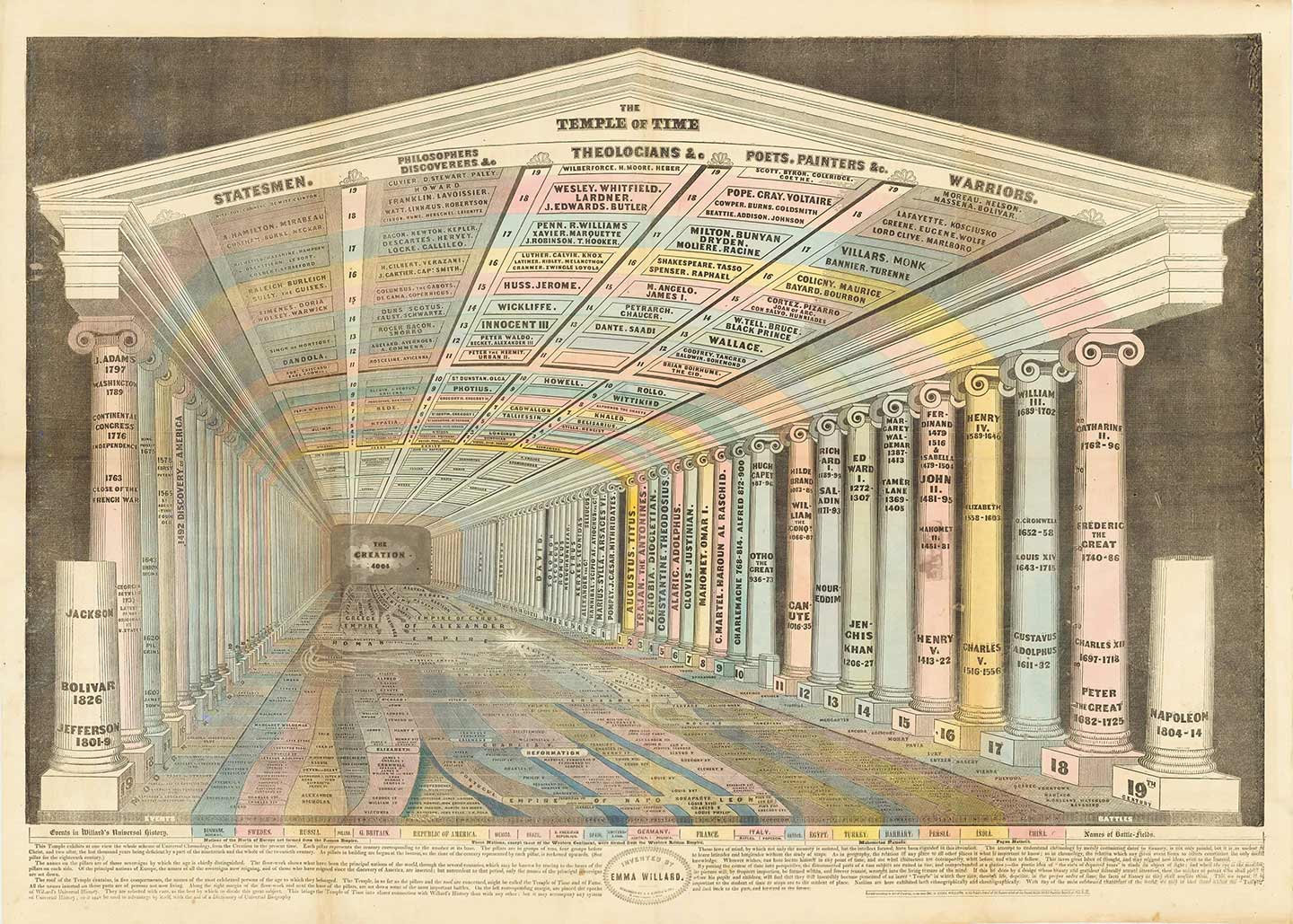

As a Graphic Designer for Film & TV, I work in the art department and create anything that is seen on screen with text and or imagery, such as storefront signs, food packaging, patterned wallpaper, stacks of bills, newspapers, lost cat flyers, or even children’s drawings. The range of items we create is incredibly broad, and the cool thing about that is it reframes graphic design from an exclusive, professional pursuit into a universal human activity. If everything is design, everyone is a designer. So instead of creating as “Leah Spencer, graphic designer,” I have to create as a shopkeeper, as a sign painter, as a college student, as an accountant, and so on.

Some of the many items considered graphic design in the context of film and TV. In addition to designing these items, the graphics team is also responsible for physically making them in-house or sending them out to a vendor for fabrication.

Considerations for Typography

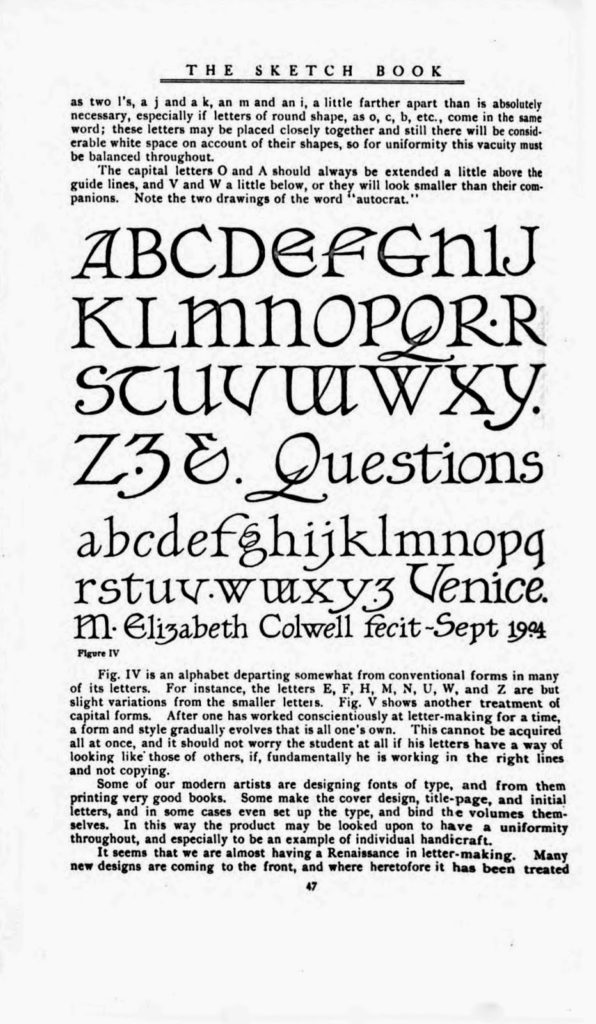

In addition to the challenges of forgery, I specialize in graphic design for period productions, and when you approach period typography, you wind up with several restrictions. Firstly, many typefaces that were used for letterpress or used in typewriters were never digitized and only survive today in their original forms or in their printed materials. Secondly, there are lots of existing digital period typefaces like Futura or Garamond, but they too have issues. We lack (or are logistically unable to use) historical production methods, such as mimeograph, Letraset, offset printing, Linotype, etc., so the kind of roughness you expect of period graphics is lost. We also have legal restrictions on font foundry use, so each production’s clearance team will tell you, for example, “you can only use Adobe fonts on this movie.” This can be restrictive, particularly for period or highly stylized productions where only a small portion of the available fonts are appropriate. And thirdly, there are lots of instances of lettering that were never a typeface in any sense, such as sign painting or handwriting.