This is the last part of the series, “What does a feminist graphic design history in the United States look like? Read Part 3 here, Part 2 here and Part 1 here.

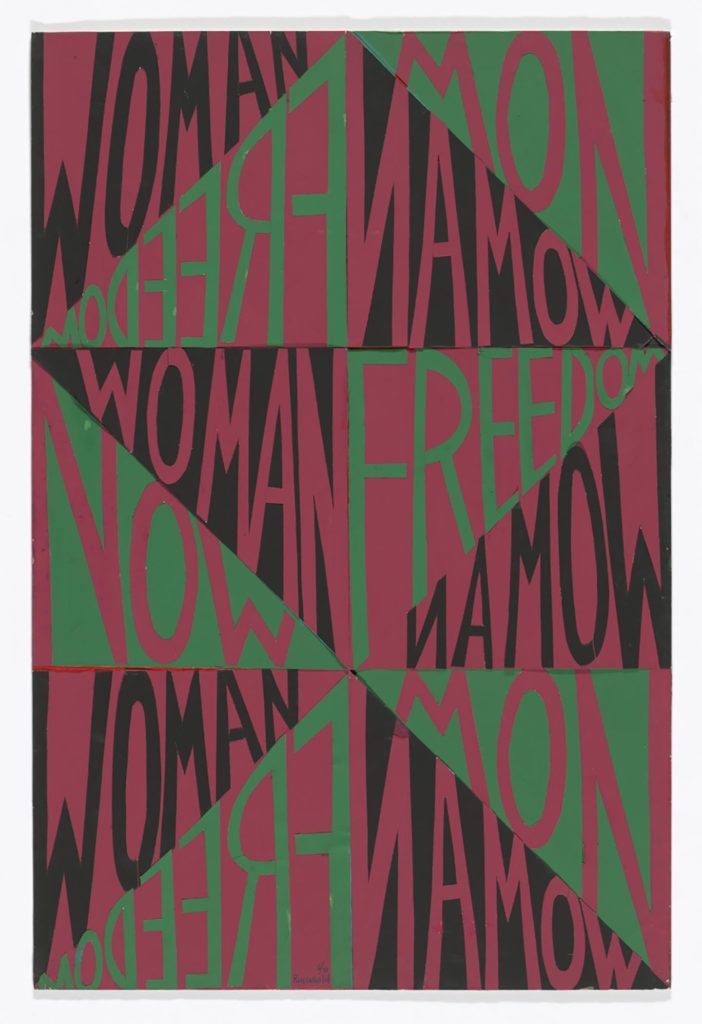

Because the assumption of universal and pseudo-neutral design is ultimately blind to nuances, visual alternatives emerged from countercultures. During the second wave feminism movement in particular, feminist design aimed to engage and connect in an experimental, interdisciplinary, participatory, non-hierarchical and non-authoritarian way, which broke the principles of the existing male value-constructs of “good” design. It is exciting to think of how design could be more egalitarian by discovering these alternative universes with those who were left out of design history.

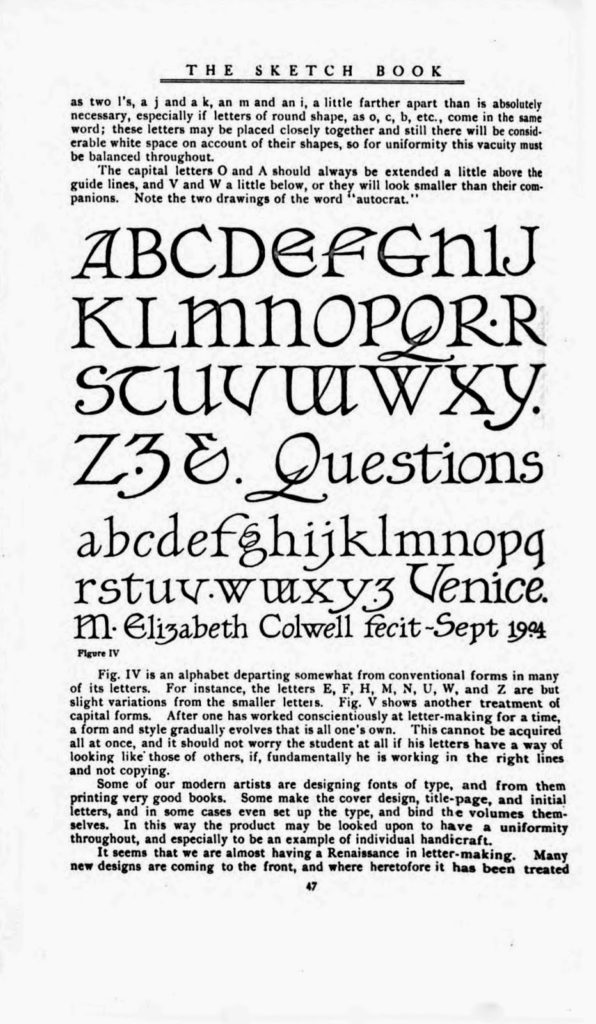

Modern Typography

Faith Ringgold, Woman Freedom Now, 1971, Accessed March 21, 2020: https://www.moma.org/collection/works/202866