At the end of June, I was lucky to attend the new Centre for Printing History and Culture (CPHC) conference ‘Script, print, and letterforms in global contexts: the visual and the material’. Organised at the Birmingham City University in the UK by the talented Sahar Afshar, Vaibhav Singh, and Darryl Lim, the conference set out to explore the ‘plurality of engagements with, and interpretations of the printed and written word in various writing systems and artefacts’.

Maybe it was the anticipation of attending a conference’s first edition, or the large range of fascinating topics on the conference schedule. Or perhaps it was the idea of visiting the ‘Brummies’ in Birmingham, with its beautiful industrial terracotta buildings. Whatever the origin, I was already excited about this conference long before it even started. And I can confirm that it totally lived up to my expectations.

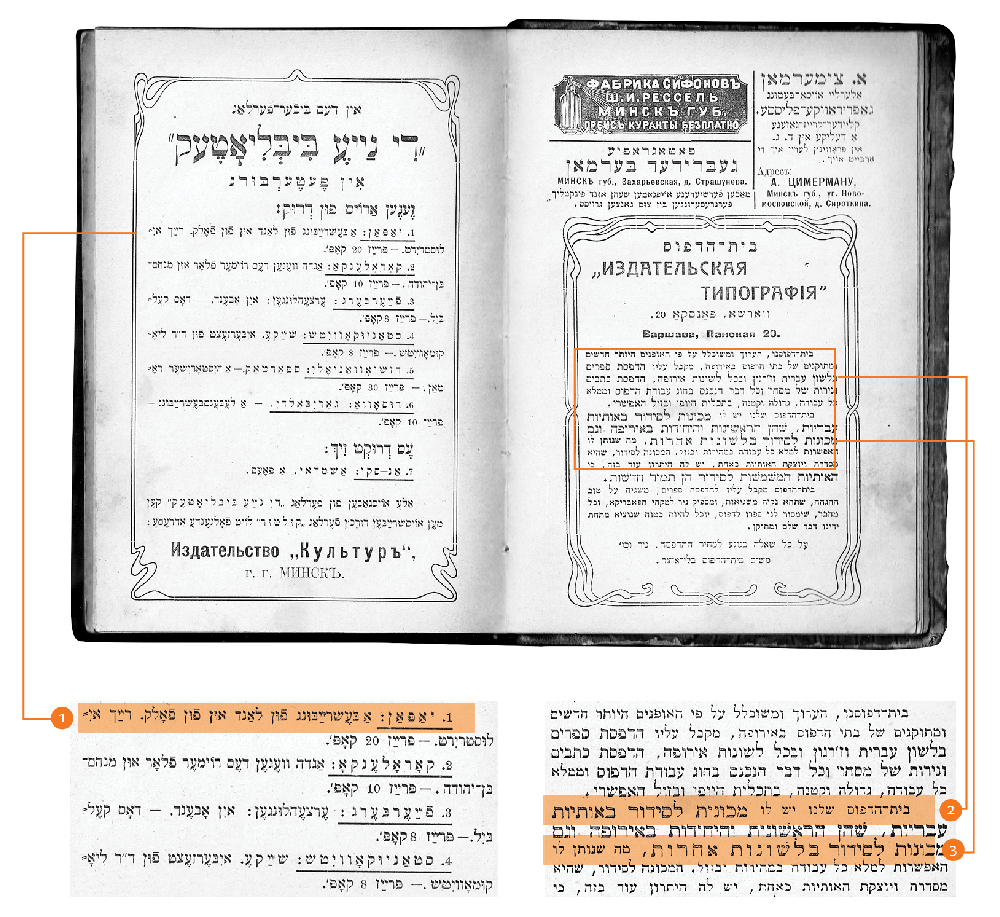

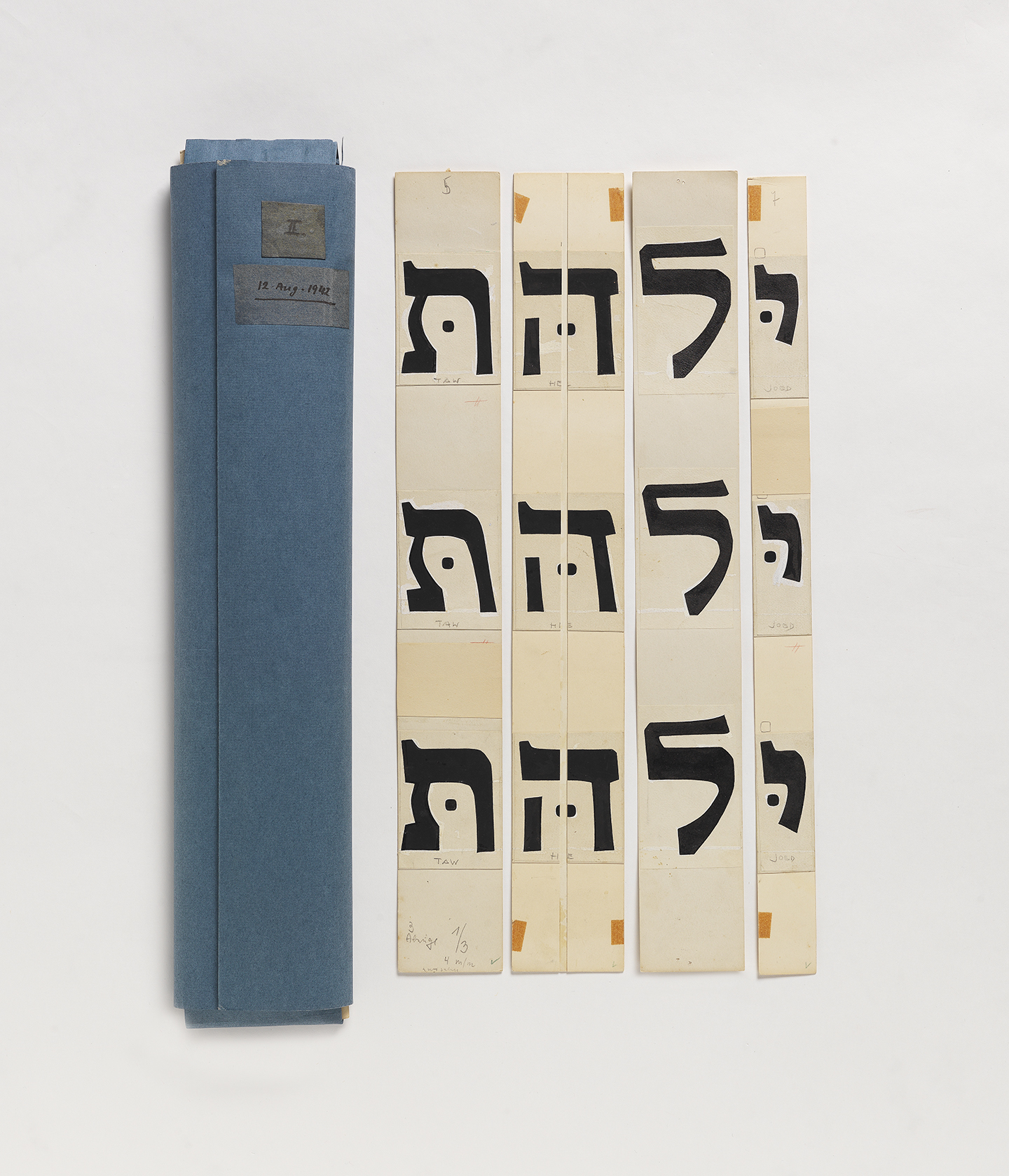

It’s the smallest conference I’ve ever attended, and probably the most eclectic. With a crowd of roughly 50 attendees and speakers, its ambition was no less than that of a larger conference. Bringing together scholars and practitioners from various disciplines such as book history, printing, publishing, type design, typography, and print culture, the conference aimed to start conversations from different points of view on print ‘in the diverse linguistic contexts of the world’.